A PRESENT FOR REGINE OLSEN AT THE TIME SHE WAS ENGAGED TO KIERKEGAARD

CHRISTIAN WINTHER.

Danske Romanzer, hundrede og fem. Samlede og Udgivne. [Danish Romances, One Hundred and Five. Collected and Issued].

Kjøbenhavn, H.C. Klein, 1839.

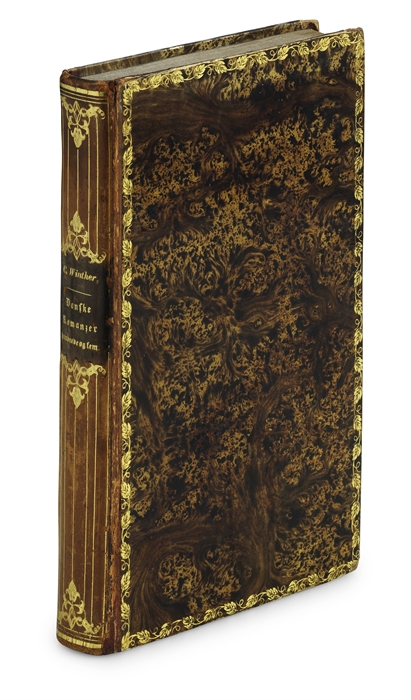

8vo. Bound in a magnificent, contemporary full mottled calf binding with exquisitely gilt spine, Gothic gilt lettering to spine (author in Latin lettering, title in Gothic lettering) and boards with a lovely, romantic border of gilt leaves. Lovely blue end-papers. Very light wear to spine and slight wear to corners. A small, almost unnoticeable restoration to lower front hinge. An absolutely exquisite copy in wonderful condition. Internally some brownspotting. (6), 386 pp.

Jørgen Bertelsen’s book-plate to inside of front board.

First edition of Christian Winther’s lovely collection of Danish romantic poems, with the very neat and meticulously written ownership signature of the young Regine Olsen ("Regina Olsen") - Søren Kierkegaard's fiance and lifelong muse - to front free end-paper. The name that has gone down in history as one of the most important muses in philosophy, Regine, is also frequently known – perhaps even more significantly so – in the variation Regina. From February 2nd, 1839, e.g., we have the now so famous Kierkegaardian praise of the woman: “You, my heart’s sovereign mistress stored in the deepest recesses of my heart, in my most brimmingly vital thoughts, there where it is equally far to heaven as to hell–unknown divinity! Oh, can I really believe what the poets say: that when a man sees the beloved object for the first time he believes he has seen her long before, that all love, as all knowledge, is recollection, that love in the single individual also has its prophecies, its types, its myths, its Old Testament? Everywhere, in every girl’s face, I see features of your beauty, yet I think I’d need all the girls in the world to extract, as it were, your beauty from theirs, that I’d have to criss-cross the whole world to find the continent I lack yet that which the deepest secret of my whole ‘I’ magnetically points to – and the next moment you are so near me, so present, so richly supplementing my spirit that I am transfigured and feel how good it is to be here…” (EE :7 1839, SKS 18, 8). Here, Kierkegaard plays with the name of his beloved, his “mistress”, whose name in Latin (with an “a”) means queen. The entry originally merely had “my heart’s sovereign mistress”, but afterwards, Kierkegaard inserted the name of her – the one –, Regina, the queen of his heart. This has been the source of much interpretation. Some see in this the onset of the transformation of the actual, physical girl into the poetically spiritual figure, who is doomed to never becoming anything but that of which immortal writing is made. (See e.g. Garff, Regines Gåde, p. 46). Kierkegaard also elsewhere alludes to Regina (see NB3 :43 1847, SKS 20, 268) and in a draft of a letter to Schlegel from 1849, where he wishes to rekindle contact with Regine, of course with the approval of her husband (who did not accept), he refers to her as “a girl, who poetically deserves to be called Regina”, ending the passus with telling Schlegel that he makes her happy in life, whereas Kierkegaard will secure her immortality. (SKS 28, 255). Regine herself, perhaps prompted by Søren’s use of it, would also later sign herself Regina (see letters to her sister Cornelia sent from the West Indies). It is evident from the ca. 30 letters we have from Kierkegaard to Regine, covering the engagement period (September 1840-October 1841), that during that period, Søren would occasionally send Regine presents along with his letters. These presents include flowers, perfume, a scarf, a copy of the New Testament, candle sticks, a music rest, and a “painting apparatus”. But we know little of what could have come before. Could there have been an actual engagement present? Kierkegaard does not mention it in his diaries nor in any letter still known or preserved. What would he have given her? It is pure speculation, but it does not seem unreasonable that he would have given her a book – a recently published one – that contains some of his favourite romantic poems from some of his favourite Danish poets, poets that he quoted in his love letters to Regine, a book compiled by the poet he treasured more than anyone else, Christian Winther, and which also contained poems by one of the people he treasured the most as a person, a near father figure for him and one of the finest poets (and philosophers) in Denmark, Poul Martin Møller … Had he given her one such book, it would have been beautifully, exquisitely, and possibly slightly romantically bound. And she would have written her name in it – with all probability, seeing that it came from him, the name that he gave her in 1839 – Regina Olsen. This lovely publication by Christian Winther of Danish romantic poems contains extracts of the loveliest of Danish golden age romantic poetry. Apart from Winther’s own six contributions, the collection contains romances by all the greatest Danish poets of the period, among them Hans Christian Andersen, Baggesen, Grundtvig, Hauch, Heiberg, Ingemann, Poul Martin Møller, Paludan Müller, Oehlenschläger, and others. In the present work of Danish romantic poems gathered by Winther we find all but 2), which was only published the year after, in 1840. Added to that is another lovely detail, namely that Regine at the end of letter 139 to her from Kierkegaard has written a little quotation herself, namely part of a poem from Johannes Ewald’s Fiskerne (see SKS 28, 226,27). That exact part of the larger work Fiskerne, entitled Liden Gunver, from which Regine here quotes, is also to be found in the present work of Danish romances. REGINE OLSEN It is safe to say that Regine Olsen occupies a place like none other in Kierkegaard’s life. Their love story is one of the most intriguing in the history of intellectual thought and has always been an inevitable source of fascination for anyone interested in understanding Kierkegaard. It is not so much the love story itself, the engagement, and the rupture of the engagement that is responsible for the lasting importance that Regine has come to have upon Kierkegaard-reception and -scholarship, as it is Kierkegaard’s own, endless reflections upon it and his constant insistence that she – the one – is the reason he became the writer that he did. Regine is inextricably linked to Kierkegaard’s authorship, and in his own eyes, she became the outer, historical cause of it. It is not only in his journals and in letters to his confidantes that Kierkegaard keeps returning to Regine, their story, and the ongoing importance she holds for him, her unique position in his authorship is evident both directly (as in the preface to his Two Upbuilding Discourses from 1843, where he imagines how the book reaches the one) and more indirectly, albeit still clearly alluding to her in e.g. Repetition, Either-Or, Fear and Trembling, Philosophical Fragments, etc. “Even though Regine is not mentioned by her legal name one single time in the authorship, she twines through it as an erotic arabesque. In poetical form she appears before the reader in works such as Repetition, Fear and Trembling and Guilty? – Not Guilty [i.e. in Stages on Life’s Way], which in each their way thematizes different love conflicts, but she can also show herself quite unexpectedly, e.g. deep inside philosophical Fragments, where it is said about the relationship between god and man that “The unhappy lies not in the fact that the lovers could not have each other, but in the fact that they could not understand each other.” (Gert Posselt, in Lex, translated from Danish). One of the most striking passages is from Repetition, where Constantin Constantius explains the paradox of loving the only one, but still having to end the relationship and how the loved one became the cause of his writing career: “The young girl whom he adored had become almost a burden to him; and yet she was his darling, the only woman he had ever loved, the only one he would ever love. On the other hand, nevertheless, he did not love her, he merely longed for her. For all this, a striking change was wrought in him. There was awakened in him a poetical productivity upon a scale which I had never thought possible. Then I easily comprehended the situation. The young girl was not his love, she was the occasion of awakening the primitive poetic talent within him and making him a poet. Therefore he could love only her, could never forget her, never wish to love anyone else; and yet he was forever only longing for her. She was drawn into his very nature as a part of it, the remembrance of her was ever fresh. (Lowrie, 1946, p. 140). It is no wonder that anyone interested in understanding Kierkegaard is also interested in understanding the relationship with Regine. According to Kierkegaard himself, there would not be the Kierkegaardian opus we have today, were it not for Regine Olsen – “the importance of my entire authorial existence shall fully and absolutely fall upon her” (draft of a letter, see: Mit Forhold til Hende, p. 116). Due to numerous letters and a wealth of journal entries, we have a very vivid picture of how Kierkegaard got engaged and what happened afterwards. Kierkegaard wanted us to know. He wanted posterity to know the significance that Regine and the relationship with her had upon his life and work. A few of Kierkegard’s journal entries about Regine are redacted – some things have perhaps become too personal for prosperity to read, or Kierkegaard had later wished to put the story in a slightly different light –, but the rest gives a very clear picture of both the engagement and Kierkegaard’s afterthoughts. And about the continuous role of both her and the rupture of the engagement in his authorship and personal life. Added to that, we also have many of the letters that Kierkegaard sent to Regine during their engagement period. A few years after the engagement ended, Regine got engaged to and later married the Government officer Fritz Schlegel, who got stationed in the Danish West Indies, where they lived from 1855 to 1860. Kierkegaard died the very same year that Regine left Denmark, and after his death, Regine received in the post the bundle of letters that Kierkegaard had written to her, along with the letters he wrote to his friend Emil Boesen concerning Regine as well as Kierkegaard’s Notebook 15, entitled My Relationship with “her”. When Søren and Regine’s engagement ended, it seems that they each gave back to the other the letters that they had written. Regine says that she burnt hers (see Raphael Meyer) – some speculate, however, that maybe she did not after all and that they might be out there in the world somewhere, but none of them have ever surfaced –, and Kierkegaard kept his, for Regine later to do with as she wanted. Regine kept the letters and the Notebook 15 and for years did nothing with them. But she did not destroy them. As she got older, she decided to pass them on to someone she trusted, and in 1893, she visited Henriette Lund (Kierkegaard’s favourite niece) and told her that she wished for her to be entrusted with the notebook and the letters. According to Henriette Lund, by the following year, Regine had given the matter some more thought and had decided that Henritte Lund should publish the letters, also parts of those to Boesen and parts of Notebook 15. The publication was to also include conversations she had with Regine about the engagement. The fruit of this is the book entitled Mit Forhold til Hende (My Relationship with Her) by Henriette Lund, which was finished in 1896 and published after Regine’s death, as agreed, in 1904. We do not know exactly what happened, but it seems that Regine was not completely satisfied with the collaboration, and in 1896 she turned to Raphael Meyer and asked him to “listen to what “an old lady” could have to tell”, write down everything about the engagement period, along with the publication of the letters, the letters to Boesen, and the contents of Notebook 15. This work too appeared in 1904, after Regine’s death, and is more complete than Henriette Lund’s publication. Thus, although this enormously important relationship seems to be somehow still shrouded in mystery and Kierkegaard followers still hunt for Regine’s diary from the period and the allegedly burnt letters that may contain groundbreaking new information that will let us understand the great existentialist philosopher and somehow solve the “mystery”, the Søren-Regine relationship is very well documented, from both sides. This does not make it any less interesting. There is a reason why it occupies Kierkegaard so deeply throughout his life. And why it continues to occupy the rest of us. It all begins in 1837, when Kierkegaard meets the lovely young girl Regine Olsen when paying a call to the widowed Cathrine Rørdam. Three years later, in September 1840, after having corresponded frequently with her and visited her on numerous occasions, Kierkegaard decides to ask for her hand in marriage. She and her family accept, but already the following day, Kierkegaard regrets his decision and agonizes endlessly over it, until finally, in October 1841, he breaks off the engagement. Or at least intentionally behaved in such a manner that Regine had no other choice but to break it off. Disregarding the scandal, the heartbreak (his own included), and the numerous pleas from family members and friends alike, Kierkegaard’s tortured soul, still searching for God and for the meaning of faith, cannot continue living with the promise of marriage. Once again, he says in his journals from 1848, looking back, he had been flung back to the abyss of his melancholy, because he did not dare believe that God would take away the underlying misery of his personality and rid him of his almost maddening melancholy, which is what he wished for with the entire passion of his soul, both for Regine’s and thus also for his own sake. (See Pap. 1848, p. 61). Later the same month, he flees Copenhagen and the scandal surrounding the broken engagement. He leaves for Berlin, the first of his four stays there, clearly tortured by his decision, but also intent on not being able to go through with the engagement. As is evident from his posthumously published Papers, Kierkegaard’s only way out of the relationship was to play a charming, but cold, villain, a charlatan, not betraying his inner thoughts and feelings – the relationship had to be broken and Kierkegaard had to be gruesome to help her – “see that is “Fear and Trembling” “ (Not 15:15 1849, SKS 19, 444). Despite the brevity of the engagement, it has gone down in history as one of the most significant in the entire history of modern thought. It is a real-life Werther-story with the father of Existentialism as the main character, thus with the dumbfounding existentialist outcome that no-one could have foreseen. This exceedingly famous and difficult engagement became the introduction to one of the most influential authorships in the last two centuries. It is during his stay in Berlin, right after the rupture of the engagement, that he begins writing Either Or, parts of which, like Repetition, as we have noted above, can be read as an almost autobiographical rendering of his failed engagement. Several of Kierkegaard’s most significant works are born out of the relationship with Regine – and its ending. And she is constantly at the back of his head, the backdrop to all of his writings. She was the reason for my authorship”, Kierkegaard writes, “Her name shall belong to my writing, remembered for as long as I am remembered”, “Her life had enormous importance”, “Neither history nor I shall forget you”, “In history she will walk by my side”, “She shall belong to history”, and so we could go on establishing the enormous importance of Regine through quotes from Kierkegaard’s diaries and letters. “– she has and must have first and only priority in my life – but God has first priority. My engagement to her and the break is in fact my relationship to God, is, if I dare say so, divinely my engagement to God.” (NB27 :21, SKS 25, 139). With good reason, many view Regine as the key to Kierkegaard’s authorship. Without Regine, not only none of Kierkegaard’s writings, but also no absolute relationship to God.

In his love letters to Regine, Kierkegaard will occasionally quote Danish romantic poems. These are often by either Christian Winther or Poul Martin Møller, arguably the two poets he treasured the most, but he will also quote Baggesen and Grundtvig. During the year of the engagement – from 1840 to 1841 –, in the letters to Regine that are preserved (as noted above), Kierkegaard quotes the following Danish poems:

Brev 130: Poul Martin Møller, Den Gamle Elsker (SKS 28, 217,6)

Brev 131: Winther, Violinspilleren ved Kilden (SKS 28, 217,22)

Brev 131: Poul Martin Møller, Den gamle Elsker (SKS 28, 218,30)

Brev 138: Baggesen, Agnete fra Holmegaard (SKS 28, 224,24)

Brev 139: Poul Martin Møller, Den gamle Elsker (SKS 28, 225,24)

Brev 145: Winther, Henrik og Else (SKS 28, 232,12)

Brev 150: Grundtvig, Vilhelm Bisp og Kong Svend (SKS 28, 239,21)

This all might be pure coincidence. But we find it speaks to more than that. Even though nothing can be concluded as to exactly who gave Regine the present book, there is no doubt that she treasured this beautifully, romantically bound volume with some of the loveliest Danish poems, in which she wrote her name so beautifully in her youth, presumably right around her first engagement. As is evident from the auction record, Kierkegaard too owned a copy of the present book, albeit not in a dainty binding.

Provenance: From the Thielst-family.

Order-nr.: 62336

![Danske Romanzer, hundrede og fem. Samlede og Udgivne. [Danish Romances, One Hundred and Five. Collected and Issued].](/images/product/62336b.jpg)

![Danske Romanzer, hundrede og fem. Samlede og Udgivne. [Danish Romances, One Hundred and Five. Collected and Issued].](/images/product/62336c.jpg)