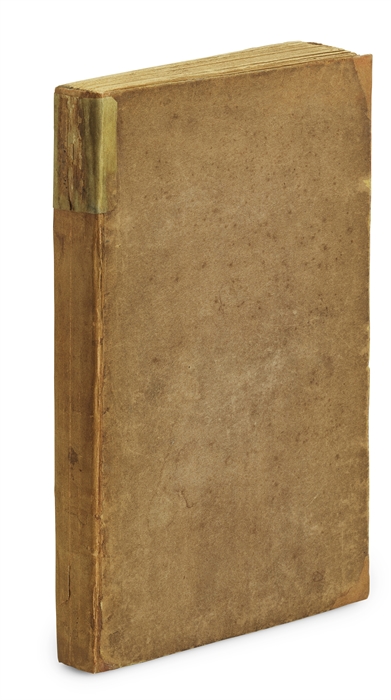

KIERKEGAARD’S DISSERTATION IN THE ORIGINAL BINDING, WHICH IS OF THE UTMOST SCARCITY.

KIERKEGAARD, SØREN.

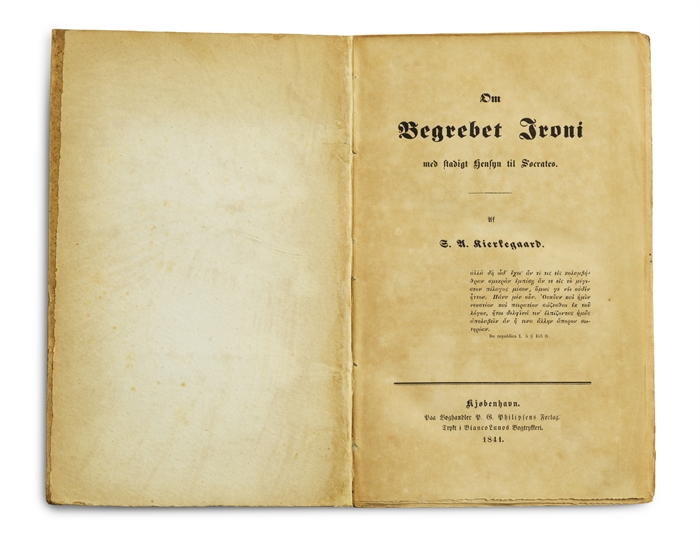

Om Begrebet Ironi med stadigt hensyn til Socrates. Af S. A. Kierkegaard.

Kjøbenhavn, P.G. Philipsens Forlag, 1841.

8vo. (4), 350 pp., 1 f. (blank), 2 pp. (advertisements). Completely uncut and partly unopened in the original brown cardboard binding. Rebacked with paper perfectly matching that of the boards. Corners restored. Title-page evenly browned and a few leaves with a bit of brownspotting, but overall in unusually nice condition, clean, fresh, and bright. Completely unmarked.

A fabulous copy of the first edition of Kierkegaard’s dissertation, here in the original binding, which is of the utmost scarcity. We have only seen it in this state once before. And of all the copies we have handled of the Irony over the last decades, we have only once before come across a copy with the advertisement-leaf in the back. This is virtually never present. This completely uncut copy is approximately 1 cm taller and wider than regular copies. The spines of the original Kierkegaard cardboard bindings are always just thin paper directly glued on the block, making them extremely fragile, especially on the thicker volumes. If one finds these original bindings, the spines are almost always more or less disintegrated. Kierkegaard's dissertation constitutes the culmination of three years’ intensive studies of Socrates and “the true point of departure for Kierkegaard’s authorship” (Brandes). The work is of the utmost importance in Kierkegaard’s production, not only as his first academic treatise, but also because he here introduces several themes that will be addressed in his later works. Among these we find the question of defining the subject of cognition and self-knowledge of the subject. The maxim of “know thyself” will be a constant throughout his oeuvre, as is the theory of knowledge acquisition that he deals with here. The dissertation is also noteworthy in referencing many of Hegel’s theses in a not negative context, something that Kierkegaard himself would later note with disappointment and characterize as an early, uncritical use of Hegel. Another noteworthy feature is the fact that the thesis is written in Danish, which was unheard of at the time. Kierkegaard felt that Danish was a more suitable language for the thesis and hadto petition the King to be granted permission to submit it in Danish rather than Latin. This in itself poses as certain irony, as the young Kierkegaard was known to express himself poorly and very long-winded in written Danish. One of Kierkegaard’s only true friends, his school friend H.P. Holst recounts (in 1869) how the two had a special school friendship and working relationship, in which Kierkegaard wrote Latin compositions for Holst, while Holst wrote Danish compositions for Kierkegaard, who “expressed himself in a hopelessly Latin Danish crawling with participial phrases and extraordinarily complicatedsentences” (Garff, p. 139). When Kierkegaard, in 1838, was ready to publish his famous piece on Hans Christian Andersen (see nr. 1 & 2 above), which was to appear in Heiberg’s journal Perseus, Heiberg had agreed to publish the piece, although he had some severe critical comments about the way and the form in which it was written – if it were to appear in Perseus, Heiberg demanded, at the very least, the young Kierkegaard would have to submit it in a reasonably readable Danish. “Kierkegaard therefore turned to his old schoolmate H. P. Holst and asked him to do something with the language…” (Garff, p. 139). From their school days, Holst was well aware of the problem with Kierkegaard’s Danish, and he recounts that over the summer, he actually “translated” Kierkegaard’s article on Andersen into proper Danish. The oral defense was conducted in Latin, however. The judges all agreed that the work submitted was both intelligent and noteworthy. But they were concerned about its style, which was found to be both tasteless, long-winded, and idiosyncratic. We already here witness Kierkegaard’s idiosyncratic approach to content and style that is so characteristic for all of his greatest works. Both stylistically and thematically, Kierkegaard’s and especially a clear precursor for his magnum opus Either-Or that is to be his next publication. The year 1841 is a momentous one in Kierkegaard’s life. It is the year that he completes his dissertation and commences his sojourn in Berlin, but it is also the defining year in his personal life, namely the year that he breaks off his engagement with Regine Olsen. And finally, it is the year that he begins writing Either-Or. In many ways, Either-Or is born directly out of The Concept of Irony and is the work that brings the theory of Irony to life. Part One of the dissertation concentrates on Socrates as interpreted by Xenophon, Plato, and Aristophanes, with a word on Hegel and Hegelian categories. Part Two is a more synoptic discussion of the concept of irony in Kierkegaard’s categories, with examples from other philosophers. The work constitutes Kierkegaard’s attempt at understanding the role of irony in disrupting society, and with Socrates understood through Kierkegaard, we witness a whole new way of interpreting the world before us. Wisdom is not necessarily fixed, and we ought to use Socratic ignorance to approach the world without the inherited bias of our cultures. With irony, we will be able to embrace the not knowing. We need to question the world knowing we may not find an answer. The moment we stop questioning and just accept the easy answers, we succumb to ignorance. We must use irony to laugh at ourselves in order to improve ourselves and to laugh at society in order to improve the world. The work was submitted to the Philosophical Faculty at the University of Copenhagen on June 3rd 1841. Kierkegaard had asked for his dissertation to be ready from the printer’s in ample time for him to defend it before the new semester commenced. This presumably because he had already planned his sojourn to Berlin to hear the master philosopher Schelling. On September 16th, the book was issued, and on September 29th, the defense would take place. The entire defense, including a two hour long lunch break, took seven hours, during which ”an unusually full auditorium” would listen to the official opponents F.C. Sibbern and P.O. Brøndsted as well as the seven “ex auditorio” opponents F.C. Petersen, J.L. Heiberg, P.C. Kierkegaard, Fr. Beck, F.P.J. Dahl, H .J.Thue og C.F. Christens, not to mention Kierkegaard himself. Two weeks later, on October 12th, Kierkegaard broke off his engagement with Regine Olsen (for the implications of this event, see the section about Regine in vol. II). The work appeared in two states – one with the four pages of “Theses”, for academics of the university, whereas the copies without the theses were intended for ordinary sale. These sales copies also do not have “Udgivet for Magistergraden” and “theologisk Candidat” on the title-page. The present copy is one of the sales-copies without theses. Himmelstrup 8 The present copy is no. 11 in Girsel's "Kierkegaard" (The Catalogue) which can be found here.

Order-nr.: 62112