FROM NAPOLEON'S LIBRARY

PRONY, (GASPARD CLAIR FRANCOIS RICHE de).

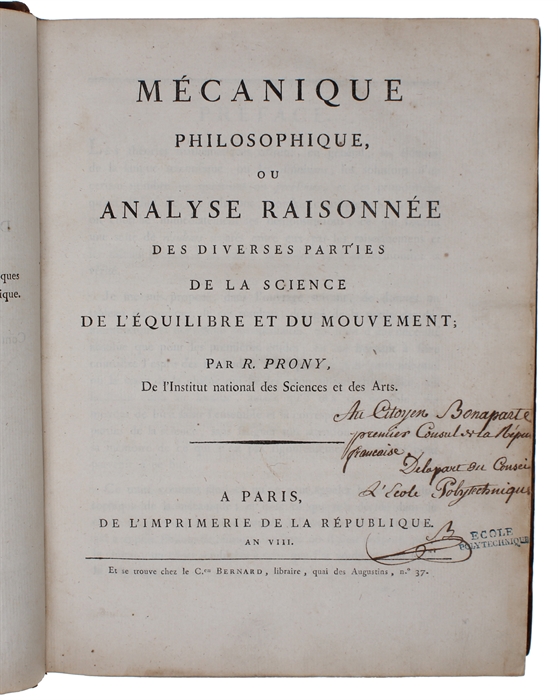

Mécanique Philosophique, ou Analyse Raisonnée des diverses parties de la Science de l'Équilibre et du Mouvement.

Paris, Imprimerie de la République, an VIII [i.e. 1800].

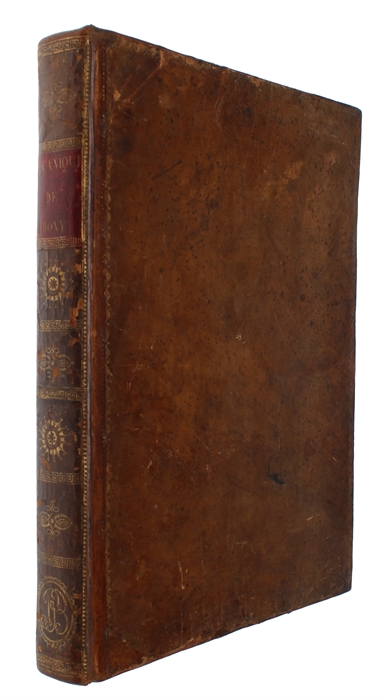

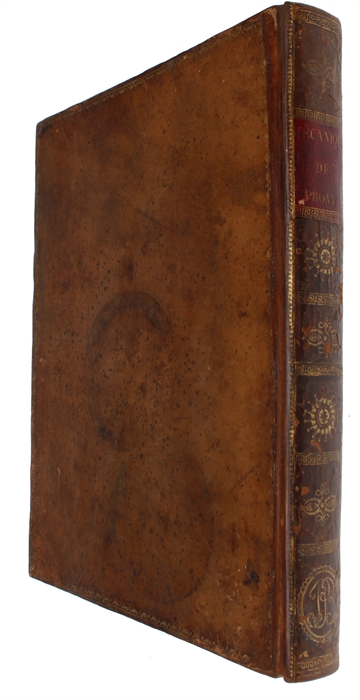

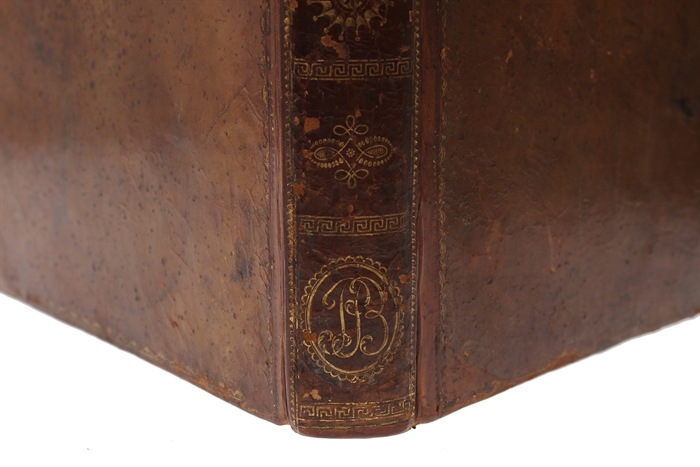

4to. Bound in a lovely full mottled calf binding with fine, gilt ornamental borders to boards, double gilt line-borders to all edges of boards and a richly gilt spine. Spine with gilt red leather title-label and with the gilt monogram of Joséphine and Napoléon - "JB" - to lower spine. Neatly rebacked.

With a handwritten inscription for Napoleon to title-page "Au Citoyen Bonaparte/ premier Consul de la République francaise/ De la part du Conseil [de]/ L'Ecole Polythechnique", with a signature underneath and the stamp of the Ecole Polytechnique. The inscription is slighly cropped at the outer margin. A bit of brownspotting here and there. (4), VII, (1), 477, (3) pp.

First edition, original offprint from Journal Polytechnique, Tome III, Cahiers 7 & 8, of Prony's magnum opus "Mécanique phlilosophique". The three parts here are all that appeared, as the planned two parts announced on the verso of the extra title-page never appeared. A truly splendid copy from Napoleon's library, with the gilt monogram of him and Joséphine from the library at Malmaison and with a presentation-inscription for Napoléon, which is rare. Books from the library at Malmaison do occasionally appear on the market, although they are rare. They are usually taken to be mainly Joséphine's, as she spent more time there. This, however, is a rare exception. First, we know that Napoléon actually did spend time at Malmaison at the time that he was given the present volume, around 1800, second, it bears an inscription for him, which is rare, determining for a fact that this was one of his books, not Joséphine's. Together with the Tuileries, Malmaison was the French government's headquarters from 1800 to 1802, exactly the time that Napoleon will have been given the present book and incorporated it in his library. Many of the books at the Malmaison library were books on things like gardening that Joséphine cared a great deal about. These were clearly her books. And some of the books, like the present, were clearly those of Napoleon himself. Napoleon was a voracious reader and he spent much time in his library studying his books. He had a personal librarian, always travelled with books, and took pride in constructing portable libraries as well as the rooms for his own actual library. On 9 July 1800, he gave the commission for a study to be built in place of the three small rooms situated on the south corner pavilion of Malmaison. Fontaine removed the partition walls and commissioned the Jacob brothers to make the teak woodwork. On 18 September, Fontaine wrote: “Everything is now in place, and even though the First Consul found that the room looked like a church sacristy, he was nevertheless forced to admit that it would have been difficult to do better in such an unsuitable space”. The paintings of the great ancient and classical authors which surround Apollo and Minerva on the ceiling were probably executed by Lafitte. Napoleon had been an avid reader since he was quite young, and when he began studying at the École Militaire in Paris, he continued to read classics, literature, and philosophy, as he would throughout his life, but he also read more scientifically and strategically aimed books. “His appetite for reading books continued as he rose in power. In 1798, about to depart on the Egyptian campaign, he gave Bourrienne a list of books he wanted in his camp library. These included works in Sciences and Arts (e.g., Treatise on Fortifications), Geography and Travels (e.g., Cook’s Voyages), History (e.g., Thucydides, Frederick II), Poetry (e.g., Ossian, Tasso, Ariosto), Novels (e.g., Voltaire, Héloïse, Werther and 40 volumes of “English novels”), and Politics and Morals (the Bible, the Koran, the Vedas, etc.)” (Shannon Selin: Bonaparte the Book Worm), giving us a great insight into his preferences at the time. Prony, with his great Mechanical Philosophy, will have fallen perfectly amongst these great writers, when Napoleon returned to Malmaison, combining politics, science, and philosophy. It is not difficult to see how Napoleon will have been intrigued by mechanical philosophy, which is a form of natural philosophy that compares the universe to a large-scale mechanism. Mechanical philosophy is associated with the scientific revolution of Early Modern Europe, and one of the first expositions of universal mechanism is found in the opening passages of Hobbes’s Leviathan. Prony, in the present work, argues that mechanical principles in the practical arts themselves call for philosophical analysis. Baron Gaspard de Prony (1755-1839) was a French mathematician and engineer. He was educated at the Benedictine College at Toissei in Doubs. From there, he entered the École des Ponts et Chaussés in 1776, where he studied engineering until graduating in 1779. “In 1780 he became an engineer with the École des Ponts et Chaussés and after three years in a number of different regions of France he returned to the École des Ponts et Chaussés in Paris 1783. This was the same year he published his first major work in the Académie des Sciences on the forces on arches. Monge was impressed with this paper and realised that de Prony was someone of great potential. […] In 1794 the École Centrale des Travaux Publics was founded by and was directed by Carnot and Monge. It was renamed the École Polytechnique in 1795 and de Prony was certainly one of the main lectures by this time. He is listed among the first teachers at the university […] In 1798 de Prony refused Napoleon's request that he join his army of invasion to Egypt. Fourier, Monge and Malus had agreed to be part of the expeditionary force and Napoleon was angry that de Prony would not come. It did mean that de Prony was to fail to receive the honours he deserved from Napoleon but de Prony's wife was a close friend of Joséphine and this probably saved de Prony from anything worse. In 1798 de Prony achieved his ambition of being appointed director of the École des Ponts et Chaussés. His desire for this post was almost certainly a main reason for his refusing to join Napoleon. As director he began producing a number of important texts on mathematical physics.” (From University of St. Andrews scientific biographies). The present book and its presentation to Napoleon comes from this time, linking the two even closer. After Napoleon was defeated, the reorganization in France included a reorganization of the École Polytechnique, which was closed during 1816. De Prony lost his position as professor there and was not part of the reorganization committee. However, as soon as the school reopened, de Prony was asked to be an examiner so he continued his connection yet only had to work one month per year.

In 1785 de Prony visited England on a project to obtain an accurate measurement of the relative positions of the Greenwich Observatory and the Paris Observatory. Two years later he was promoted to inspector at the École des Ponts et Chaussés. Around this time he was involved with the work on the Louis XVI Bridge in Paris which is now called the Pont de la Concorde.

Further promotion in 1790 was followed the next year by his being appointed Engineer-in-Chief of the École des Ponts et Chaussés. This promotion was as a result of the opening of the Louis XVI Bridge.

Also around 1791 de Prony was working on geometry with Pierre Girard. Then in 1792, de Prony began a major task of producing logarithmic and trigonometric tables, the Cadastre. With the assistance of Legendre, Carnot and other mathematicians, and between 70 to 80 assistants, the work was undertaken over a period of years, being completed in 1801.

Order-nr.: 60104