THE FIRST TEXTBOOK OF PHYSIOLOGY

DESCARTES, RENATUS.

De Homine Figuris et latinate donatus a Florentio Schuyl, Inclytæ Urbis Sylvæ Ducis Senatore, & ibidem Philosophiæ Professore.

Lugduni Batavorum (Leyden), Apud Petrum Leffen & Franciscum Moyardum, 1662.

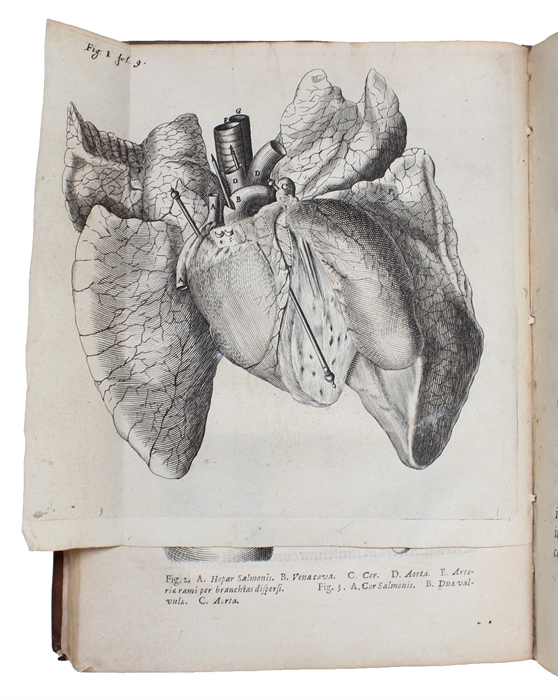

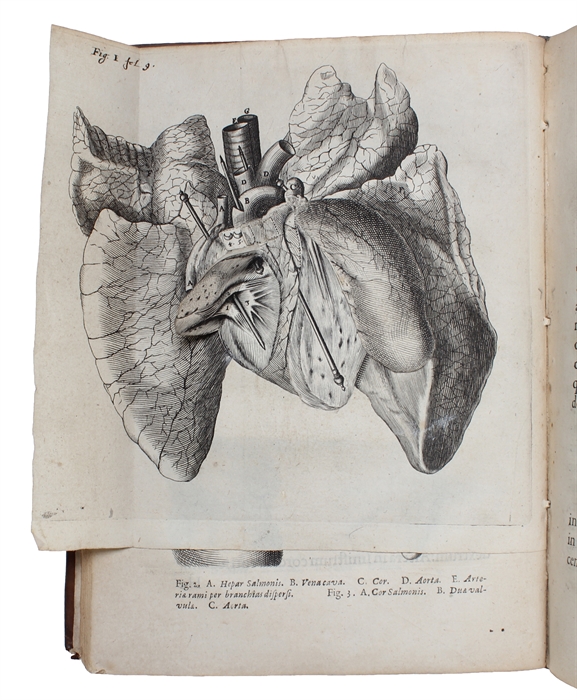

4to. Contemporary full calf with gilt title-laebl to spine. (36), 121, (1) pp. + 10 plates. Complete with all 56 woodcut and engraved text-illustrations (many of which are full-page) and the 10 full-page engraved plates (several folded), one of which is the heart-plate with the 6 moveable parts, the Cardiac-flaps (of which only the smallest is missing). One folded plate cropped at fore-margin.

First edition of Descartes' seminal treatise on man, the first European textbook of physiology, constituting an epochal work of modern thought, defining the mechanism of man as it does. "In the Treatise of man, Descartes did not describe man, but a kind of conceptual models of man, namely creatures, created by God, which consist of two ingredients, a body and a soul. "These men will be composed, as we are, of a soul and a body. First I must describe the body on its own; then the soul, again on its own; and finally I must show how these two natures would have to be joined and united in order to constitute men who resemble us"." (SEP).

This highly influential work was the first to present a coherent description of bodily responses in neurophysiological terms that are still, to a wide extent, accepted today.

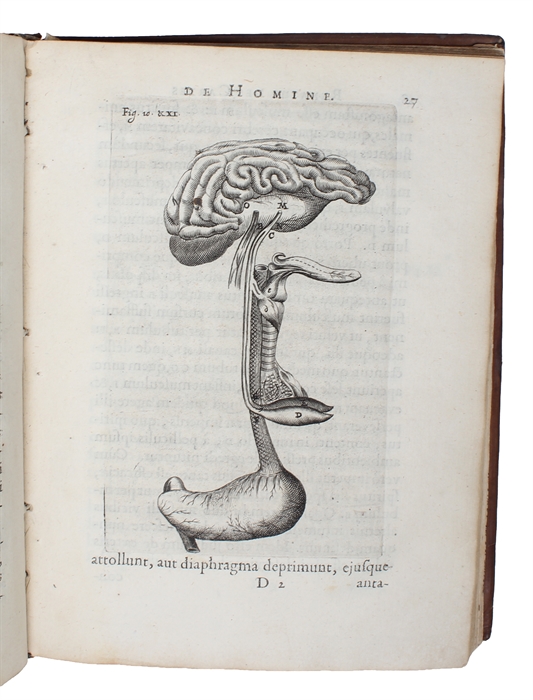

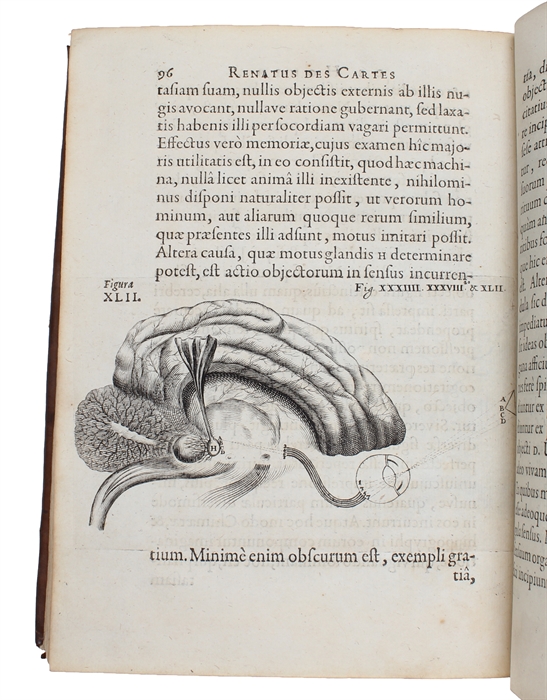

In his attempt to solve the central question around which almost all philosophical thought had revolved since the time of Aristotle, what the relation between the soul and the body actually is, Descartes came to create a milestone work of physiology which changed the entire trajectory of modern physiological conceptions. "Without Descartes, the seventeenth-century mechanization of physiological conceptions would have been inconceivable." (DSB). He believed that the relationship between the soul and the body was mediated by the brain and the nervous system, and his seminal attempts to explain neural mechanisms drew a great deal on the engineering developments of his time (eg. the hydraulic automata that had been installed at the Versailles). He developed a hydro-mechanical theory of how the soul controlled the contraction of muscle through the intermediary of the pineal and the cerebral ventricles, and he produced an explanation of how it received, through the nerves from the periphery, signals that gave rise to sensation. Descartes' theories quickly spread throughout Europe, and the work in which he had developed them, his "De Homine" became extremely influential.

This posthumously published work was actually written in the 1630's, but after the condemnation of Galilei in 1633, Descartes did not dare publish it; "although it thus had to await posthumous publication in the 1660's, his writing of the Traité de l'homme proved extremely important in the further maturation of Descartes's physiological conceptions." (D.S.B. p.62).

"Some time after Descartes's death in 1650, his French manuscript, copies of which had circulated among his friends and correspondents, was edited and published. The first version was a Latin translation (De homine) by Florentius Schuyl in 1662, the second the now better known 'original' French version (Traité de l'homme) edited by Descartes's self-appointed literary executor Claude Clerselier in 1664. In the seventeenth century the 1662 Latin version was probably much more widely read than the French text. There were problems for the editors of both versions. Firstly, there were differences between the manuscripts: Clerselier in Paris claimed that his version was Descartes's own, that the others were 'corrupt' and that Schuyl had been 'misled' by them. However, a more important difficulty was raised because it was clear that the text was intended to be illustrated - Descartes refers to figures and to features within these labelled by letters. But no set of figures accompanied the manuscripts. Both editors have left quite detailed accounts in their long prefaces - little treatises in themselves. Here I consider only Schuyl, the editor of the Latin De homine. Schuyl (1619-69) was a professor of philosophy in the town of 's-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands, the country in which Descartes was living during the writing of Le monde. Two of the author's friends had copies of the manuscript that they supplied to Schuyl, and with one of these were included two sketches of illustrations apparently in Descartes's own hand. These Schuyl included. One of them represents the medial and lateral rectus muscles in the orbit, which deflect the eye nasally and temporally. The other figures Schuyl had to have made and, since he mentions no one else, one supposes that he designed them himself." (IML Donaldson, J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2009; 39:375-6).

Wellcome II:453; Osler 931; Garrison and Morton 574. Waller only has a later edition.

Order-nr.: 52487